Making

a list of the top ten of anything seems futile. Lists like that are

subjective – what I like may make others go, “Meh.” Also, what

makes this week's list may not make next week's. Plus it's probably

not reasonable to limit lists to ten choices – Top Ten is an

advertising gimmick that we've all bought into a little too readily.

Having

said that, I have to admit that there is one good reason to

make a list of your top ten favorites of something, and that's to

give exposure to things you like, promoting them to people who may

enjoy them. That's why I've decided to list my top ten favorite

movies. My real list of favorites is way too long, but I'll pick the

ten that occur to me as I write this. They're in no particular order

– but there is one movie that I consider to be the most perfect

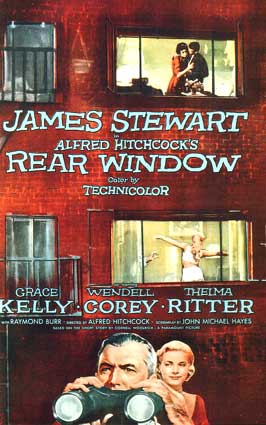

movie ever made, so I'll put it at the top of the list. It's Alfred

Hitchcock's version of Rear Window.

A

perfect movie has to take the best possible advantage of its medium,

which is primarily visual. It has a finite amount of time to tell

its story, so each frame has to count – there can be no unnecessary

scenes or shots. It has to have an excellent cast. And the story

has to be good enough to make you keep your eyes on the screen the

whole time, wondering what's going to happen next. If it isn't a

silent film, the score has to complement the visuals rather than

detracting from them. If you can do all that, you've made a perfect

movie.

If

you watch Hitchcock's Rear Window, you

may be deceived into thinking that not much thought went into it.

It's so seamless, you can't see how clever it is. There are two

sets, and they blend into each other. The whole shebang – Jeff's

apartment, the courtyard, and the other apartments the main

characters can see into – was filmed on a big soundstage. The

sounds and music in the movie are ambient, what you would naturally

hear if you lived in one of those apartments. This enhances the

reality of the setting, and puts the characters and story in the

forefront. We're really there with 'Jeff' Jeffries, a world-traveling

photographer who's laid up with a broken leg and going stir crazy.

That's why we're able to see, almost from the beginning, that things

are not what they seem.

The

screenplay is based on Cornell Woolrich's short story, “It Had To

Be Murder.” Woolrich was one of the best American short story

writers of the 20th

Century, a master of suspense. John Michael Hayes' adaptation is

perfect, and I suspect it was shaped as much by the cast as it was by

the necessities of the movie medium. Grace Kelly owns the role of

Lisa – I think it's her best role ever. She's so believable, you

know she lives beyond the story, having adventures well into her 90s.

Jimmy

Stewart made several great movies with Alfred Hitchcock, including

Vertigo, an

almost-perfect movie.

Vertigo is marred by

an info-dump scene in which Kim Novak's character writes a letter

explaining a plot point. The studio insisted this was necessary,

because the executives who saw the first screening were too dumb to

figure out what was going on. If Hitchcock could have lived long

enough to see the “Director's Cut” videos that have since become

the norm, I'm sure he would have insisted on releasing a version

without that dopey letter scene in it.

Fortunately, Rear Window made it to the final cut without that sort of tampering. Complementing Kelly and Stewart is a cast of veteran character actors. Thelma Ritter shines as the visiting nurse, Wendell Corey makes you believe he's a police detective who also fought in WWII. The actors who play the neighbors whose antics are so fascinating really seem to be living the lives of those people. And Raymond Burr is one of the scariest movie killers I've ever seen.

Though

Burr is a big guy, he's not an ax-wielding, snarling, macho kind of

killer. He's clever, quiet, and sneaky. You don't get a hint of the

violence he's capable of until someone actually confronts him. Even

then, you get the feeling he'd rather not mix it up with anyone, he

just wants to get rid of the multiple packages that used to be his

wife and get on with his new life.

Stewart's

character is also not a macho guy, though he has a lot of courage.

He's never afraid to say what he thinks, but even if he didn't have a

broken leg, you get the feeling Burr could have kicked his butt.

That's what makes the final confrontation between the two so

suspenseful.

One

terrifying moment that stands out in Aliens

is the scene where the door to the freight elevator opens. You

suspect the Queen alien is crouched in that shadowy space, but you

don't know for sure until you see the light glistening on those

dreadful teeth. In Rear Window,

the cinematographer manages to achieve that effect with Raymond

Burr's glasses as he steps into Jeff's darkened apartment. Somehow,

this nerd gear is transformed into something really creepy and

threatening. Burr manages to make the salesman sound both pathetic

and dangerous when he demands to know who Jeff is and what he wants.

Rear Window doesn't have a formal score, unless you count the title sequence (“Juke Box #6”), a delightful crime-jazz piece written by Franz Waxman in the heyday of the great movie scores. Otherwise, music plays on the radio, or is sung by drunken partygoers, or is tinkered together on a piano by a struggling songwriter in his rooftop studio. The song he's working on eventually becomes an integral part of the plot, and by the end of the movie it's “Lisa's Theme.”

The

plot threads are woven into a satisfying conclusion, and Jeff and

Lisa reach a believable accord in their relationship. The ending of

the movie is every bit as perfect as the beginning. That's why Rear

Window will always make my list

of top ten greatest movies.

No comments:

Post a Comment