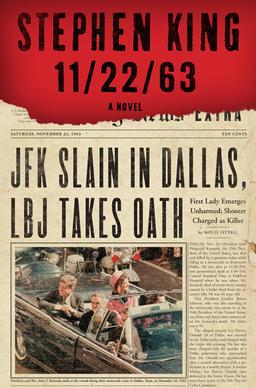

I don't usually write reviews for the books of super-popular writers. They don't need my help to get exposure, and my voice would probably get lost in the crowd. But this time around, I really feel compelled to write about Stephen King's new book, 11/22/63, not just because I liked the book so much, but also because I was so fascinated by the ideas in the book.

Like King, I lived through the early sixties. I was born in 1959, so I was only four years old when JFK was assassinated. But that event was so shattering, so enormous to ordinary American citizens, for most of my childhood it almost seemed like it had just happened. It seemed that way right into the mid seventies. Also, I lived in Phoenix, Arizona, and though it's the biggest city in Arizona, in the sixties it was a big farming community, with cotton fields stretching as far as the eye could see. Culturally speaking, we were at least a decade behind the America you could see on your TV screen. So JFK still loomed big in our world. Yet the first thing that I read in 11/22/63 that really made me think that time travel might be a wonderful thing to do was not the idea that maybe someone could go back and prevent the assassination of JFK. It was the root beer.

I could taste that root beer he described in the book. And in Arizona, that experience had an extra dimension: the root beer was ice cold. If it's 107 degrees outside, and the humidity is less than 5%, drinking an ice cold root beer is a heavenly experience. When I was a kid, I was usually on foot when I went after the root beer, and sometimes I was even foolish enough to go barefoot, though the pavement could be incredibly hot. So the root beer hunt was a perilous adventure, one that offered truly fabulous rewards.

Nostalgia clouds our memories of the past. In most books about time travel, that isn't much of an issue – people go way back in time. So in this case, it's interesting that the character is only going back about 50 years. It's even more interesting that he isn't from that decade himself, he won't be born until the mid-seventies. Nostalgia isn't driving him at all, though he certainly develops a healthy dose of it once he's able to experience that root beer, as well as other delightful artifacts. Many other artifacts he encounters are not so delightful: racism, sexism, small town bigotry, and a resistance to putting really good books like Catcher In The Rye in school libraries, where they would actually do the most good. A man without a mission might just visit the past occasionally, stick to the root beer and the inexpensive golden-age comic books, avoid the jerks as much as possible.

But Jake (masquerading as “George”) does have a mission. In fact, he has more than one, and the JFK assassination isn't even the most important one. He has another rescue driving him, one that's a lot more personal, a friend whose life was changed by one terrible night when his father murdered the entire family. The friend was the sole survivor of that massacre, and was badly injured. Jake thinks first of him, and that's a good thing. If saving JFK was the only thing on his mind, that would be some serious hubris. Thinking you can stop the massacre of a family is also hubris, but most of us would try to do the same thing if we could. And like Jake, we would find out just how dangerous and daunting that is. First of all, guys who are capable of murdering their entire families possess a terrible vitality, and above-average cunning. Most people have no idea how to fight a dragon like that. So this is one of the many challenges facing Jake.

Another challenge is that time itself seems to resist his efforts. The deck is stacked against him. Can he defeat this law of nature? Yes and no, and that's the key to this book. I don't want to spoil it for you by describing what happens, you need to sit at the edge of that seat yourself. But this story really inspired me to reconsider the concept of time travel. Most scientists will tell you it's not possible. But people also said that about traveling faster than Mach 1, and we're way past that now. If you consider that anything is possible, then you have to consider that time travel is one of those possible things. And if it's possible, what are the consequences?

When someone tampers with history, does the timeline lurch into a new path? Or is damage done on some level we can't perceive until the dissonance is so severe, the weave of time/space starts to come unraveled in some places? Will time act to protect itself? King may not be the first to ponder those questions, but his approach is not the usual one taken by writers who like to write about time travel. Many writers like to puzzle through paradoxes and loops that pinch themselves off once someone has done something that would have changed history enough that their very trip through time has been cancelled out of the timeline.

Other writers like to employ the concept of the fan-shaped destiny, with multiple possibilities radiating from pivotal moments in history. I think most people would agree that the assassination of JFK is one of those pivotal moments. When I was a kid, I believed that if only he hadn't died, all of the fine dreams he had for our country would have come true. It wasn't until the presidential election of 2000 that I started to question some of my assumptions. I heard a respected reporter say that Al Gore shouldn't waste too much time grumbling about the way the electoral process had been mangled, because he was certain to win the 2004 election.

None of the other talking heads on the program questioned that assumption, but I did. No election is ever a sure thing for any candidate. And that's when I began to wonder if Kennedy could have gotten re-elected. Without the god-like shine of an assassinated president, would there be any reason to love him with such passionate devotion (unless you were a total dweeb)? If Lincoln hadn't been assassinated, would we have built his splendid memorial and chiseled all of those inspiring words into marble? Both presidents were thoroughly despised by a lot of people. The haters pretty much had to shut up after the assassinations, unless they wanted the ire of a grieving country to turn on them (not to mention the suspicions). So you could definitely get the wrong idea about what would have happened if Lincoln and JFK had been able to continue their careers.

And the assumptions don't end there. At any given time, people tend to believe that the past was a rosy place, where life was simpler, people were more virtuous, music was superior to the popular crap people listen to “these days,” and food tasted better. Somehow, they don't remember the bad stuff.

Yet at the same time, people also assume modern people are smarter. They think we're better educated, less inclined to believe superstition, stronger, and way more hip. In fact, we're so damned hip, that if we went back in time and played some modern music for those people of the past, they would think it was the greatest thing since the invention of the wheel. In movie after movie, just such a scene plays itself out, with people of the past bopping to that wonderful, superior new stuff. Never mind that every ten years or so, the old generations lament the fact that the music of the new generation sucks, big time. Plus they dress funny and they have no manners.

Music aside, simple survival in a strange place would be the biggest challenge facing any time traveler. You would have to have workable skills, and they would not include computer programming. If you were actually able to travel back in time to show those ancient people how much smarter you are, you would probably get your head handed to you on a platter (maybe literally). If you were lucky, people would feel sorry for your stupidity – a big problem, if you're trying to keep a low profile. Sticking out like a sore thumb wouldn't just make it harder to do whatever it is you went back to do, it might even do more damage. You don't want things to come to a screeching halt while everyone stops to gape at this bozo who just showed up out of nowhere and didn't know anything. The Butterfly Effect that Ray Bradbury wrote about in “A Sound Of Thunder” (also mentioned by Jake in 11/22/63) could only get worse under those circumstances.

According to Bradbury, the Butterfly Effect would be magnified exponentially, depending on how far back you went. Yet, common sense would not necessarily stop a time traveler. You'd be asking yourself, Just how much will actually change? If I can do a greater good, will any harm that occurs as a result of people not meeting people, intersections failing to happen, new patterns emerging, be worth it? Maybe you would hope that things would be different-but-better. Or at least still okay. Or maybe you would selfishly pursue your own agenda and not give a damn.

Jake isn't selfish, though he does get wrapped up in the past. He at least has an excuse – his mission is a noble one, once he commits himself, and in the meantime, maybe he can do some good in the more ordinary lives he intersects. You don't blame him when he realizes that he's happier in the early 1960s than he was in the 21st century. But he's screwing with time, and you have to wonder how big the bill is going to be when it finally comes due. And the mission itself seems impossible – how can he stop such a gigantic event? Maybe he can't. Maybe he should just disappear into the 60s and lead his new (increasingly un-fake) life. It might not lead to a happy ending, but it might be as happy as any life can be.

But once he's seen Lee Harvey Oswald, that's no longer possible. The smaller questions generate bigger ones, until it finally all boils down to one really big question: Can Jake sacrifice personal happiness in order to save the world?

That's what you'll find out when you read 11/22/63. But I've got a question of my own. Everyone wonders how things might have turned out if things had happened differently. What if Oswald had failed to shoot Kennedy? What if the assassination attempt against Hitler had succeeded? What if someone had realized that Harris and Klebold were bat$#*t crazy in time to stop them? Would the world be a better place, or just a different one?

I'd like to go one further than that. What if time is already doing the best it can? What if, once you average it all together, everything that has happened really is the best that can happen? Some people might be discouraged or even horrified by that idea. But if you have to take the bad with the good, maybe you have to take the good with the bad, too. Maybe you have to admit that many wonderful things have happened, all of us have had at least some happiness in our lives. Medicine is better, science is exploring new frontiers, and we have centuries of art, music, and literature at our fingertips. On average, we have more time to spend with our loved ones than people have ever had, in the history of the human race.

We can instantly download good books like 11/22/63. Maybe that's the best argument of all.

One more thing – I listened to 11/22/63 as an audiobook. The reader, Craig Wasson, was wonderful. He deserves an award for his performance. I'll be looking for more of his work.

No comments:

Post a Comment